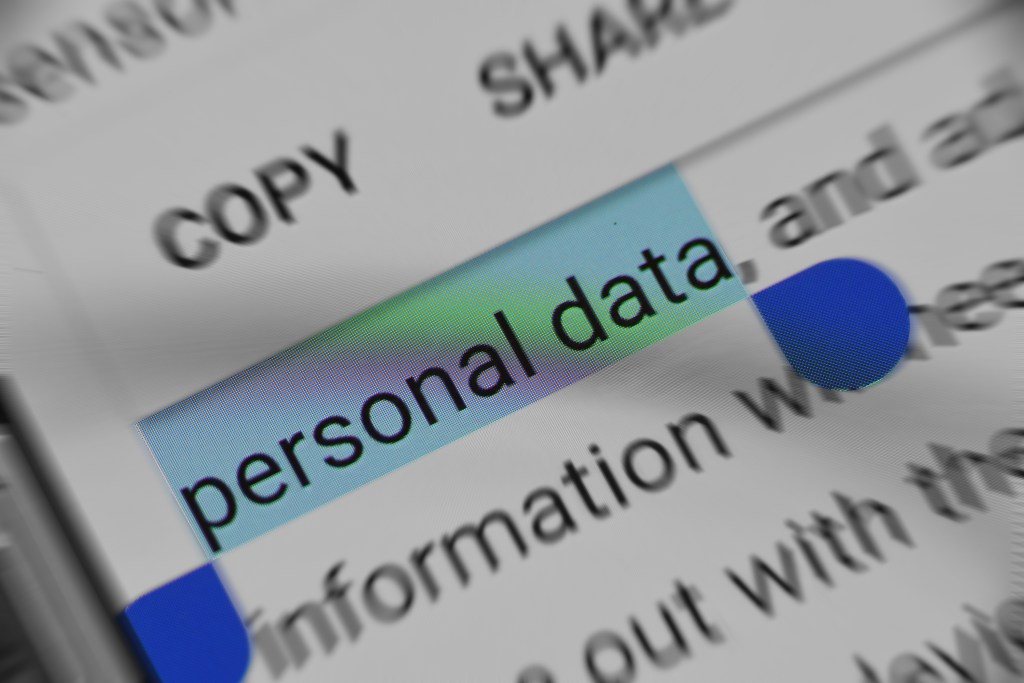

On Tuesday, the US House Committee on Energy and Commerce Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) and Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation Chair Maria Cantwell (D-WA) unveiled the bipartisan American Privacy Rights Act.

The comprehensive draft legislation sets clear, national data privacy rights and protections, eliminates the existing patchwork of state comprehensive data privacy laws, and aims to give Americans the ability to enforce their privacy rights when these are violated.

The specifics

The American Privacy Rights Act, or APRA, would limit the data that companies can collect, retain and use to only what they need to provide their products and services.

That would represent a major change from the current consent-based system that forces users to scroll through long privacy agreements and barrages them with pop-ups asking for their permission to be tracked online.

APRA would also let Americans opt out of targeted advertising and view, correct, export or delete their data and stop its sale or transfer. It would create a national registry of the data brokers that buy and sell personal information, and would require those companies to let people opt out of having their data collected and sold.

APRA would also let Americans opt out of targeted advertising and view, correct, export or delete their data and stop its sale or transfer.

By allowing consumers to opt out of data collection or even edit or delete their data, companies would be compelled to be more transparent about their data collection practices so consumers could decide what to do with their data.

One provision of the proposal would allow consumers to opt out of targeted ads — for example, advertisements sent to them based on their personal data.

“It reins in Big Tech by prohibiting them from tracking, predicting, and manipulating people’s behaviors for profit without their knowledge and consent. Americans overwhelmingly want these rights, and they are looking to us, their elected representatives, to act,” said McMorris Rodgers in a statement on Sunday.

Replacing state laws

A new bureau focused on data privacy would be created within the FTC, which would have the authority to enact new rules as technology changes. Enforcement of the law would fall to the FTC as well as state attorneys general.

One of APRA’s goals is to standardize how data is regulated across the country, replacing the laws that state legislatures have enacted during years of inaction in Congress.

Cantwell said the bill incorporates parts of state laws, including California’s and Illinois laws protecting genetic and biometric data, to set a national standard that builds on the progress made by those states.

“I think we have threaded a very important needle here,” she said. “We are preserving those standards that California and Illinois and Washington have.”

Preempting existing state laws could provoke opposition, especially from California, which enacted a pioneering data privacy law in 2018.

Despite the lawmakers’ claims that the new, nationwide privacy standard will be “stronger than any state,” actually preempting those existing state laws could provoke opposition, especially from California, which enacted a pioneering data privacy law in 2018.

Indeed, in 2022, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi refused to bring this draft bill to the floor for a vote, saying the federal version does not guarantee the same essential consumer protections as California’s existing privacy laws, but maybe also because it was opposed by Governor Gavin Newsom, a fellow California Democrat.

The proposal has not been formally introduced and remains in draft form, but the bipartisan and bicameral support for it suggests it could get serious consideration.

Basic privacy rights

Congress has long debated the ways to protect the personal data of Americans that a wide range of businesses and services collect, store and control, but partisan disputes over the details have doomed these previous proposals. Back in May 2000, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) called on Congress to pass a federal law protecting the basic privacy rights of all Americans.

That was just a few years after the internet became an everyday medium, four years before Facebook was created, and seven years before the iPhone would be introduced.

Consider what we have seen since spring 2000.

Data brokers sell the personal data of US military personnel for as little as 12 cents per record, automakers share data on drivers that are collected by their cars, and homeowner’s insurance firms take pictures of our homes’ roofs and lawns using drones. A fertility tracking app shared users’ health information with other companies, including China-based marketing firms, according to a 2023 settlement with the FTC.

Our apps make algorithmic predictions about us that can be helpful, but also have the potential for creating bias and limiting certain types of information from reaching us.

Companies get away with relying on the small print in agreements and manuals, putting the burden on consumers to read the long-winded privacy policies of hundreds of companies that collect their data, and then make privacy choices for each one of them.

Protections and carveouts can and should be afforded to small businesses – APRA does so by exempting the small entities that are not selling their customers’ personal information – but all others should be subject to consumers’ ability to control how their data is used, transferred and sold.

Although Europe and California have stepped into the vacuum to pass robust privacy laws to protect their citizens, these laws are far from enough. An issue as important and borderless as privacy deserves leadership and legal enforcement in the United States at a national level.