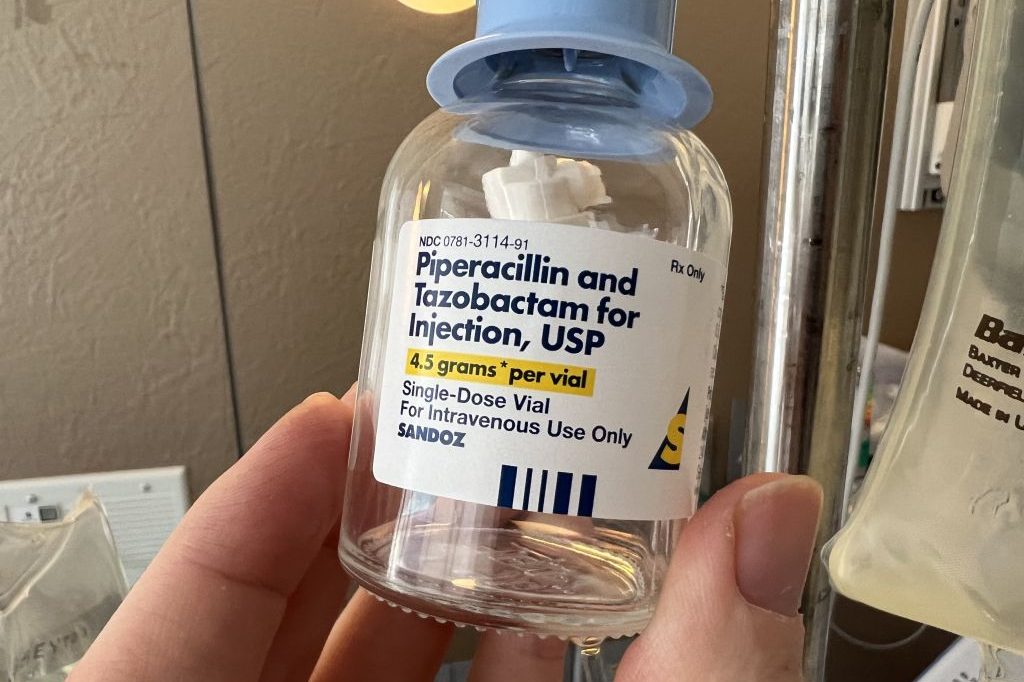

A growing coalition of US states has formally objected to a provision in Florida’s $10m settlement with generic drugmaker Sandoz, arguing it unfairly restricts their ability to negotiate independent and potentially larger payouts.

In a motion filed in federal court, 20 states plus the District of Columbia and US

The

Register for free to keep reading

To continue reading this article and unlock full access to GRIP, register now. You’ll enjoy free access to all content until our subscription service launches in early 2026.

- Unlimited access to industry insights

- Stay on top of key rules and regulatory changes with our Rules Navigator

- Ad-free experience with no distractions

- Regular podcasts from trusted external experts

- Fresh compliance and regulatory content every day