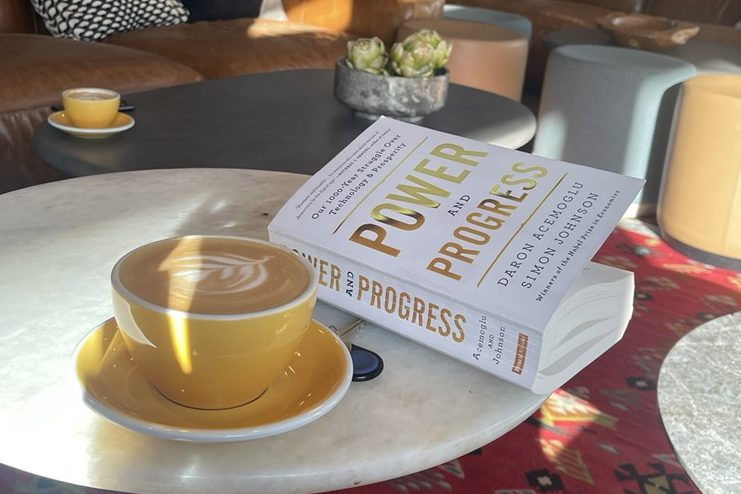

In today’s fast-moving business environment, decision-makers often seek quick, technical solutions to complex challenges. But neglecting the long view can be costly. Power and Progress is a powerful reminder of why businesses must listen to academic research, particularly when it offers historical depth.

This book provides a sweeping analysis

Register for free to keep reading

To continue reading this article and unlock full access to GRIP, register now. You’ll enjoy free access to all content until our subscription service launches in early 2026.

- Unlimited access to industry insights

- Stay on top of key rules and regulatory changes with our Rules Navigator

- Ad-free experience with no distractions

- Regular podcasts from trusted external experts

- Fresh compliance and regulatory content every day