At a glance

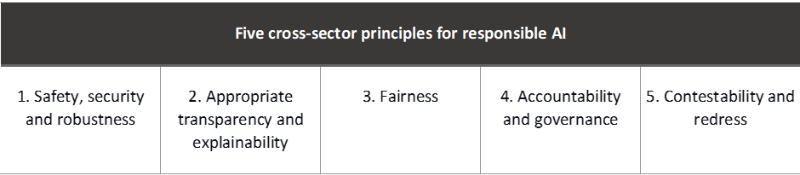

◼ On March 29, the UK Government published a consultation on its strategic approach to AI regulation. The proposals centre on a principles-based framework underpinned by five cross-sectoral principles.

◼ Companies will appreciate the additional clarity about the UK’s approach, the outcome-oriented approach, and the definition of AI based on key characteristics.

◼ The UK will not introduce a new AI regulator or enshrine the framework in law initially, opting to leverage existing regulators and legislation instead. This will support regulatory flexibility but may lead to the proposal lacking teeth and priority.

◼ The success of this framework will depend significantly on cross-regulatory collaboration and consistency in interpreting its principles across different regulators. However, there will be no statutory requirement for regulators to work together.

◼ General-purpose and generative AI models have recently dominated the news. Nonetheless, the UK proposals do not specify which regulator(s) will oversee this type of AI. For now, the UK will monitor how these innovations evolve before iterating its regulatory framework.

◼ Overall, the proposed cross-sectoral principles align with high-level international frameworks. However, the details diverge considerably from the draft EU AI Act. AI will be another area where international firms will need to achieve broadly similar outcomes across jurisdictions but comply with divergent detailed requirements.

Introduction

On March 29, the UK unveiled its eagerly-awaited consultation on its strategic approach to Artificial Intelligence (AI) regulation. Led by the newly established Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT), the proposals are a key component of the UK’s ambition of becoming “a science and technology superpower by 2030”.

Central to the UK’s strategy is a principles-based AI regulatory framework applicable across all sectors. The framework will not be set in law, at least initially. The Government argues that a non-statutory approach will allow the UK to respond quickly to AI advancements while avoiding excessive regulation that could stifle innovation.

So what are some of the key elements of the framework and its potential ramifications for regulators and businesses.

Definition of AI

A shared understanding of what AI covers is crucial to the success of any regulatory framework. The Government defines AI by referencing two defining characteristics:

- Adaptivity – AI systems have the capacity to “learn” and draw inferences that human programmers neither anticipate nor can easily understand.

- Autonomy – Some AI systems can make decisions without explicit instructions or ongoing oversight from a human.

A characteristic-based approach helps the UK avoid the drawbacks of a rigid definition, which can be too narrow, too broad, or rapidly become obsolete. It also supports the Government’s strategy of adopting an outcome-focused approach regulating the use of AI, not the overall technology.

However, the framework allows individual regulators to interpret adaptivity and autonomy and develop sector-specific definitions of AI. This of course raises the risk of diverging interpretations and definitions by UK regulators – eg, FCA or Ofcom. This could create significant regulatory uncertainty for AI applications and businesses operating across sectors.

In response, the Government pledges to support coordination amongst regulators and monitor the impact of any diverging interpretations on the application of the framework. The question is whether such coordination will be effective in the absence of a statutory duty for regulators to cooperate. As we will see, this is a challenge which extends to the rest of the framework as well.

The proposed principle-based framework: key elements

The proposed framework will be underpinned by five cross-sector principles to guide the responsible design, development and use of AI.

The Government’s preferred model for applying the principles is based on five elements:

- Existing regulators take the lead – No new AI regulator will be introduced to oversee the implementation of the framework. Instead, existing regulators like the FCA or Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) will interpret and apply the principles within their remits.

- No legislative interventions (initially) – Regulators will be expected to apply the five principles proportionately using existing laws and regulations. However, after an initial implementation period of ~12 months, the Government anticipates introducing a statutory duty for regulators to have due regard to the principles.

- Regulatory guidance – Key regulators will be encouraged to publish guidance within 12 months on interpreting the AI principles for competencies or specific use cases. Regulators will also be encouraged to publish joint guidance for AI uses that cross multiple regulatory remits.

- AI sandbox – The Government will establish an AI multi-regulator sandbox to enable experimentation and greater cooperation between regulators. A pilot will launch in the next 12 months. The pilot will focus on AI uses in a single sector (eg, telco) that nevertheless require interaction with multiple regulators (e.g., Ofcom, ICO and Competition and Markets Authority). The sandbox will expand overtime to multiple industry sectors.

- Central functions for monitoring and coordination – The Government will initially coordinate, monitor, and adapt the framework, supplementing and supporting regulator work without duplicating existing activities.

Our initial assessment

The UK proposed framework undoubtedly provides some important advantages but also poses some considerable practical challenges for both businesses and regulators.

We agree with the Government that a principle-based approach may allow for greater flexibility in responding to technological and market developments. We also welcome the emphasis on the outcomes of AI rather than a technical definition. Granting regulators autonomy in deciding whether and how to apply the principles in their domains also has merits. In principle, it could foster greater proportionality and reduce compliance costs for firms, especially start-ups and new entrants.

Success will depend on effective coordination and interpretation across regulators

The full benefits of the framework will only be realised with effective coordination between regulators, consistency of interpretation of principles and supervisory expectations of firms. We have some reservations in this regard, as collaboration is currently constrained by the existing legal framework.

For instance, the FCA or Ofcom must interpret the five AI principles to best protect consumers according to the specific sector laws they each separately oversee. This means their interpretations may not always align, causing potential conflicts – for example, with data protection, as the ICO highlighted in its consultation response. See also Deloitte paper on Building trustworthy AI for more details about key areas of interaction between conduct, data protection and ethics in financial services.

Businesses need assurance that adhering to one regulator’s interpretation will not result in compliance challenges with another. In the absence of such clarity, organisations may be discouraged from investing in or adopting AI. The government’s efforts to facilitate coordination and the cross-sector regulatory AI sandbox may alleviate some issues. The Government also confirmed it will leverage existing voluntary initiatives, such as the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF), to support regulatory dialogue. However, we believe regulators will continue to struggle with formal coordination until such responsibilities are mandated by law.

Ambiguity around regulatory oversight for foundation and general-purpose AI models

The framework is also unclear as to which regulator would take the lead in regulating general purposes or foundation AI models or use cases in sectors that are not fully regulated or adequately supervised (eg, education, employment and recruitment). In these areas appointing a specific regulator(s) to oversee the framework may have benefits. This would be similar to what EU Member States will need to do under the draft AI Act.

For the time being, the Government will monitor the evolution of foundation AI models. It aims to collaborate closely with the AI research community to understand both opportunities and risks prior to refining its AI framework.

Regulatory guidance vs industry-led standard

Challenges also arise concerning the development of individual or joint regulatory guidance. With many regulators already resource-constrained and facing AI expertise gaps, developing AI guidance within 12 months may prove difficult. Regulators need clearer direction on where to focus their efforts. For instance, the ICO suggests the Government should first prioritise research into the most valuable guidance types for businesses, such as sector-specific, cross-sector, or use-case guidance.

Currently, we see a multitude of non-statutory guidance emerging, eg for medical devices, public sector, data protection. While helpful individually, these do not provide sufficient regulatory clarity for businesses. Where they are not fully complementary or compatible, they can create further complexity or confusion for AI developers and smaller organisations.

The proposed framework is designed to be complemented by tools like AI assurance techniques and industry technical standards. The Government will promote the use of these tools and collaborate with partners, such as the UK AI Standards Hub. These tools are crucial for effective AI governance and international coordination, eg, via the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO). However, as the Ada Lovelace Institute recently emphasised, assurance techniques and standards do and should focus on managing AI’s procedural and technical challenges. Their effectiveness relies on policymakers elaborating the framework principles – such as fairness or transparency – in sufficient detail in any future guidance.

International competitiveness and international alignment

A major Government-commissioned review indicates that the UK has a narrow one-to-two-year window to establish itself as a top destination for AI development. However, the UK faces stiff competition. Other jurisdictions, including the EU, have been moving at pace to position themselves as global AI authorities. The review underscores the importance of implementing an effective regulatory framework to achieve this goal. Such a framework must be flexible and proportionate but also provide sufficient regulatory clarity to boost investment and public trust in AI. As discussed above, there are areas where the proposed framework will face challenges in achieving this balance.

Regarding international alignment, the UK’s proposed five principles closely align with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) values-based AI principles, which encourage the ethical use of AI. This should facilitate international coordination, as numerous other key international AI frameworks also align with the OECD’s framework – including the draft EU AI Act and the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) AI Risk Management Framework.

However, at a more detailed level, the UK’s approach diverges significantly in approach from other major jurisdictions. For example, the draft EU AI Act imposes much more granular and stringent requirements on organisations developing, distributing or using AI applications. This and the lack of a clear statutory footing could also pose challenges in terms of international recognition or other forms of equivalence. Embedding a voluntary principle-based framework in international industry-led standards may also be challenging.

Finally, the timelines for the finalisation of the framework are lengthy and, in some places, vague. This could further prolong regulatory uncertainty and fail to provide a minimum level of certainty needed to encourage investment or adoption.

Valeria Gallo, senior manager, innovation lead, EMEA centre for regulatory strategy; Suchitra Nair, partner, EMEA Centre for Regulatory Strategy; Nick Seeber, partner, global internet regulation lead; Aurora Pack, associate director; and Lewis Keating, director, AI governance Berkeley, Deloitte.