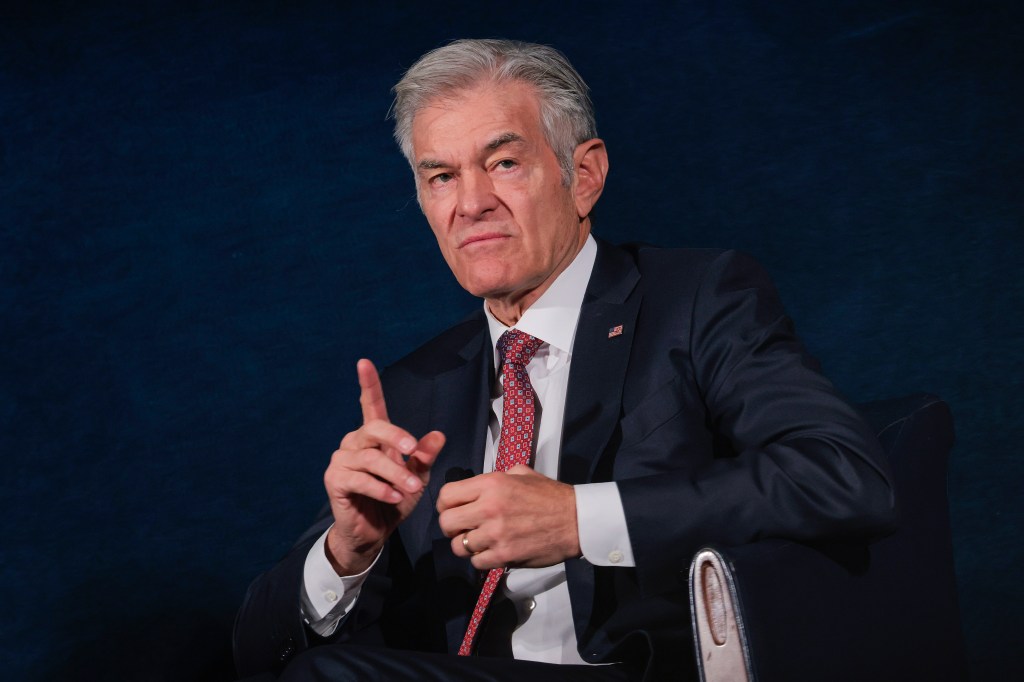

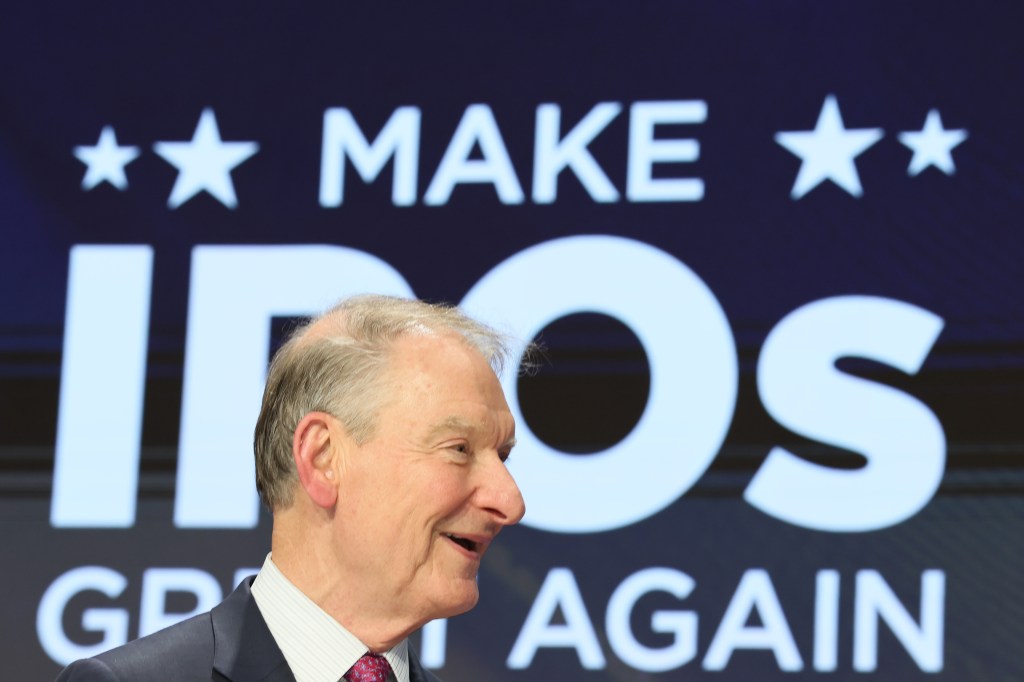

At the SEC’s Investor Advisory Committee meeting of 2025, the morning’s panel conversation turned to a fundamental challenge in modern corporate governance: how to meaningfully involve beneficial owners in proxy voting when shares are held through intermediated fund structures.

As traditional notions of shareholder democracy strain under the weight

Register for free to keep reading

To continue reading this article and unlock full access to GRIP, register now. You’ll enjoy free access to all content until our subscription service launches in early 2026.

- Unlimited access to industry insights

- Stay on top of key rules and regulatory changes with our Rules Navigator

- Ad-free experience with no distractions

- Regular podcasts from trusted external experts

- Fresh compliance and regulatory content every day