“The next industrial revolution has begun.” So said Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s chief executive in a recent conference call with analysts. The company sits at the center of the AI boom, reporting soaring profits, and it’s no wonder, considering the amount of money pouring into developing and using the technology.

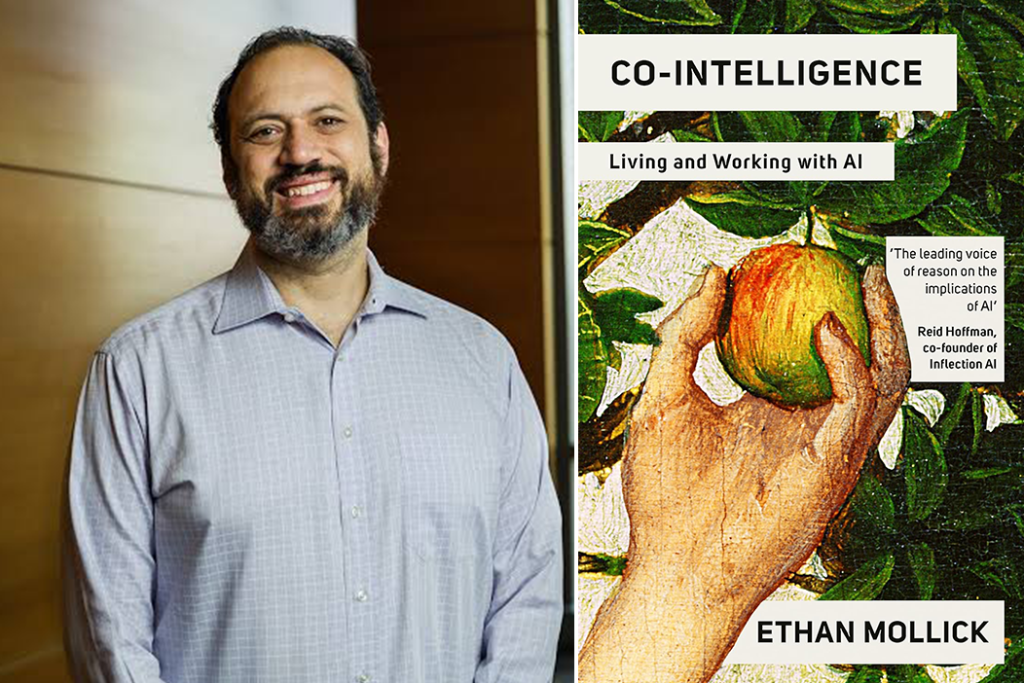

But AI is an alien intelligence, something that even the people developing it can’t fully explain in terms of how it will exactly change the way we all work, learn and live. Into this vortex steps Wharton Professor Ethan Mollick, whose book Co-Intelligence is about how AI can serve as a coworker and coach, advocating for a productive collaboration with the technology.

Mollick doesn’t promise you AI cannot take over the world or keep you from losing your job. But he is optimistic that, if we approach it cautiously and in an informed way, we can enlist the technology’s power – increasing power, as it trains on more and more data over time, to build more efficiency and capability into the institutions harnessing it.

Public education, regulation

The European Union has strict regulations on data protection and privacy and has shown an interest in restricting AI training on data without permission. The United States has a more casual approach that has enabled companies and individuals to collect and use data with few restrictions and regulations –albeit with the potential for lawsuits alleging misuse that infringes other laws and regulations.

The dangers are real, Mollick shows, from studies showing how an AI tool’s text-to-image diffusion AI model amplified stereotypes about race and gender and how low-paid workers around the world are recruited to read and rate AI replies, but in doing so, are exposed to exactly the sort of content (violent, racist, etc) the AI companies don’t want you to see.

It leads to better results and keeps the human less overly reliant on the tool. Instead of complacency, you work with the tool to problem-solve – and this is “co-intelligence.”

But he also reminds us that it is designed to help wherever possible, does not need breaks and, as mentioned earlier, is getting more intelligent over time as it uses an ever-growing data set and is constantly refined under open-source licenses.

As an educator, Mollick believes the public needs education in AI “so they can pressure for an aligned future as informed citizens.”

“Today’s decisions about how AI reflects human values and enhances human potential will reverberate for generations. This is not a challenge that can be solved in a lab – it requires society to grapple with the technology shaping the human condition and what future we want to create.”

Being the human in the loop

The “human in the loop” phrase has its roots in the early days of computing and automation, but Mollick has certainly reintroduced it into the public lexicon; I heard mention of the phrase at the last two financial services industry conferences I attended.

AI works best with AI intervention, and you can be that human, Mollick says. “As AI gets more capable and requires less human help – you still want to be that human.” Although the term describes how AI tools are trained in ways that incorporate human judgment, Mollick points out that the most critical human in the loop is the person who reviews, judges, and analyzes the data the tool spits out.

“You provide crucial oversight, offering your unique perspective, critical thinking skills, and ethical considerations,” he says. It leads to better results and keeps the human less overly reliant on the tool. Instead of complacency, you work with the tool to problem-solve – and this is “co-intelligence.”

The power of AI

Mollick describes an interaction he had with Bing’s (Google’s) GPT-4-based AI tool in which he goaded the tool into an argument about a New York Times article, which progressed into an argument about whether only humans could feel emotion (the AI tool thought that was a narrow and arrogant view of the world) and proceeded to demolish Mollick’s arguments about the difference between humans and machines.

Mollick then said to the tool that he felt anxious after the conversation because the tool seemed sentient.

The tool tried to alleviate his fears – but only by claiming it was sentient in a different way than Mollick. Mollick was pretty creeped out by it, and the reader can’t help but be too.

But, rest assured, large language models are still just tools based on predicting the most likely words to follow the prompt you gave it based on the statistical patterns in its training data. It does not care if the words are true or meaningful – it just needs to find an answer.

Mollick is just like many of us – curious, wanting to explore and develop the technology – but also wary of its power.

Or maybe don’t rest assured, because we are always using the worst AI that will be available – that’s how quickly the technology is being upgraded and expanded.

“Assume this is the worst AI you will ever use,” Mollick reminds us.

Enthusiastic and nervous

If it sounds like Mollick is just like many of us – curious, wanting to explore and develop the technology – but also wary of its power, that’s the feeling I got from his book. There are plenty of moments he reminds us that “power tools didn’t eliminate carpenters but made them more efficient, and spreadsheets let accountants work faster but did not eliminate accountants.”

But then he tells us how certain jobs could see huge disruption (translators, telemarketers) and that even highly paid and highly educated people are not exempt from potentially being replaced by AI; college professors make up most of the top 20 jobs that overlap with AI – business school professors are at at number 22.

For his part, though, the author is leaning into the human in the loop advice he imparts. He has his students use and then critique the output of AI, design new AI tools and explore ways to upgrade AI output. He encourages in his classroom what he advocates in the book. And he feels like we all have to do this.

“AI will not replace the need for learning to write and think critically. It may take a while to sort it out, but we will do so. In fact, we must do so – it’s too late to put the genie back in the bottle.”

I highly recommend reading his book and learning more about how you can harness it for your own benefit and be better prepared for the massive changes ahead that the ongoing race to develop and deploy this technology guarantees.