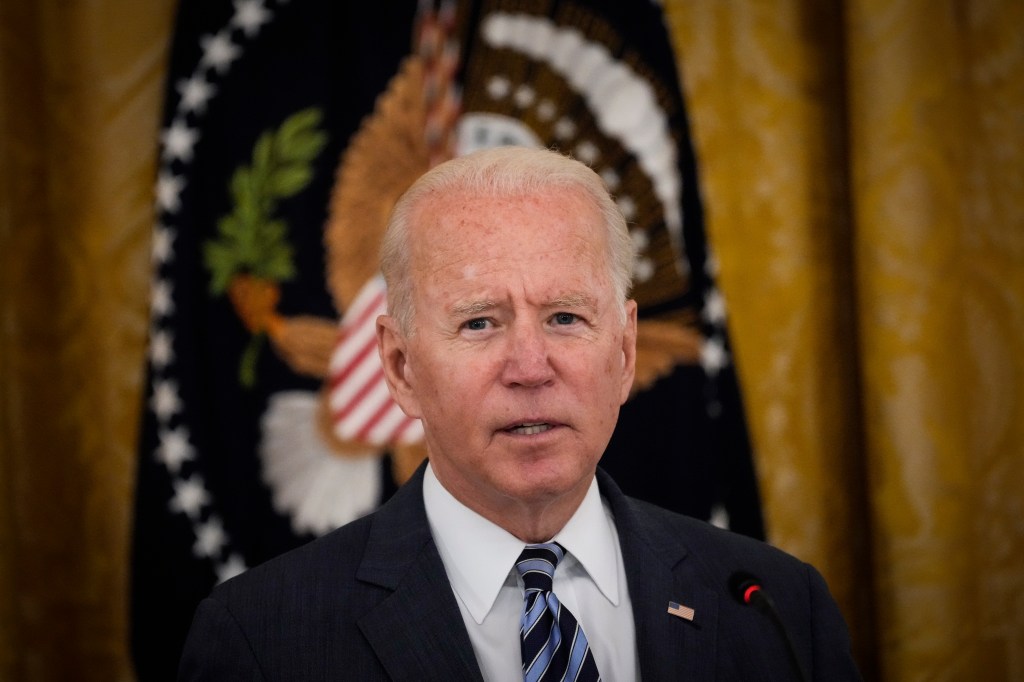

An array of notable technology companies is expected to sign an agreement this week to build stronger security into their software from the start of development. The move is part of the Biden administration’s national cybersecurity strategy.

The 65 tech companies that have pledged to sign it include Alphabet’s Google, Amazon’s AWS, Cisco, Palo Alto Networks, IBM and Microsoft. The agreement was drafted by the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), and it will be unveiled at the RSA Conference in San Francisco this week.

Under the pledge, companies commit to incorporate seven cybersecurity best practices into the development cycle of their products.

These include building and managing disclosure programs for software vulnerabilities, making patches easier to install by customers, tracking intrusions by hackers, mitigating flaws across common areas in software design, reducing the use of default passwords and enabling multifactor authentication across products as standard.

Software security by design

The US government’s plan is to boost software security by design, implementing the terms of the White House’s National Cybersecurity Strategy (published last March), which aims to shift more security responsibility onto the software manufacturers.

The CISA pledge includes examples of how to achieve a particular objective and ways to measure implementation. Signatories are expected to report publicly on their progress within one year of signing, but the manner in which companies do this, and the order in which they tackle the pledge’s objectives, is largely left up to them.

“Their agreement to hold themselves accountable is, I think, what makes this such an important and groundbreaking event for technology safety and cybersecurity,” said CISA director Jen Easterly.

Companies won’t face penalties for falling short, she said, given CISA isn’t a regulatory agency, but public pressure is expected to keep them on track.

Software security issues at US agencies

The idea for this cybersecurity agreement gained ground after a series of vulnerabilities in commonly used software were exploited by hackers to breach government agencies and companies, including Microsoft and Ivanti.

The hack of Ivanti’s products led to a hack of CISA itself, and the agency was forced to take some of its own systems offline in February as a result.

“Certainly, the incident that occurred in the last 90 days, as I’ve stated publicly, has been humbling and caused us to take a much harder look at our security stance and our relationship with CISA,” said Jeff Abbott, chief executive of Ivanti, which is one of the pledge signatories.

Shouldering the blame

At the RSA event, Bob Lord, a senior technical adviser at CISA, said it was imperative to overcome accepted norms in regard to software security. Those were that the security burden is placed on the end users, who are least able to understand the threat landscape, protect themselves, and respond to incidents.

He noted that when software vulnerabilities are exploited, the focus tends to be on blaming the victims – for example, for not patching fast enough or not deploying multi-factor authentication.

The companies that develop products are the ones that can best afford and implement a sophisticated cybersecurity program and shoulder a larger responsibility for cyber defense generally, Lord noted.

CISA’s newfound role

Last month, CISA published long-awaited draft rules on how critical-infrastructure companies must report cyberattacks to the government. The rules were inspired in part by the 2020 SolarWinds hack, which highlighted the lack of information made available to the federal government about a breach that affected a critical infrastructure entity.

It also represented one of the first steps by CISA to take on a more regulatory than advisory role.