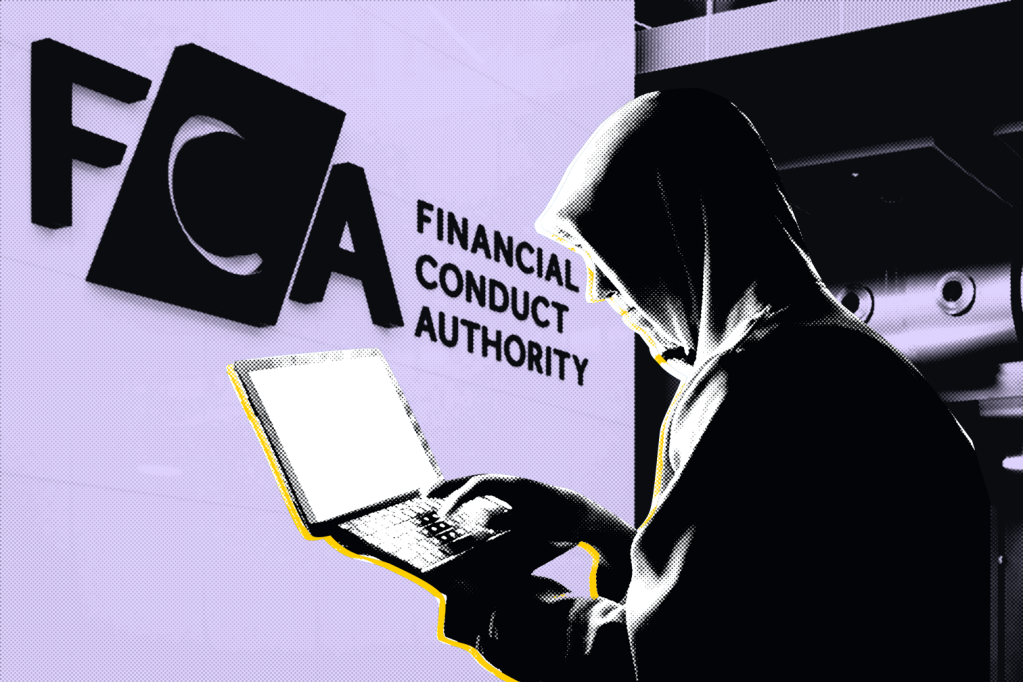

The UK’s financial watchdog the FCA recently set out its priorities for 2024, aimed in part at stemming the tide of financial crime currently blighting the UK.

The four areas it will focus on for 2024 include greater use of data and technology, fostering collaboration between sectors, raising consumer awareness and measuring the effectiveness of efforts to prevent fraud and money laundering.

The FCA has said there is a need for a collective effort involving the banks, insurers and other firms it regulates to tackle financial crime effectively. And I can only agree.

Financial crime

The appalling financial crime situation in the UK has many causes, not least of which is the lack of meaningful response from regulators such as the FCA, as well as from our law enforcement sector. In fact, many would say that the villains have already crossed the finishing line and left their pursuers in their wake.

Almost every month regulators or law enforcement bodies seem to publish new initiatives in the battle against fraudsters and money launderers. Yet to my mind these have the appearance of King Canute, trying to wish away the sea of fraud as it inexorably swamps us.

Fraud accounts for 41% of all reported crime in the UK. Less than 1% receives any policing resources and attention. The losses attributed to fraud in the UK stand in the region of £4.7 billion ($5.9 billion) a year. Given that fraud is also notoriously underreported, the true figure is likely to be much greater.

All these bodies, including the UK government, are guilty of paying lip service to tackling the huge problem before them, despite the fact that the government’s own 2023 Fraud Strategy described fraud as being a threat to national security.

Regulatory bodies such as the FCA can only do so much with the resources they have available. They want to press the financial sector to better leverage software systems and use advanced tools such as behavioral biometrics to detect and prevent fraud, for example. This is all well and good, but while the financial sector invests, the FCA and its counterparts struggle with real-term budgetary pressures.

Furthermore, while the FCA has urged the regulated sector to share information, this is (potentially) fraught with danger, given data protection laws and the need for banking secrecy. Again, why isn’t the FCA approaching the government and asking for approved conduits to be established that would enable risk-free information sharing?

It is easy to see how those in banking, insurance and other arms of the regulated sector are growing tired of rhetoric that appears to lay the majority of the blame at their door. There can be no denying they could “up” their game, but to what end?

If they spend millions on new software and identify wrongdoing, will matters be further scrutinized or prosecuted down the line? Victims of fraud need to know that if they report a crime, it will at least stand a chance of being looked at.

The suspicious activity report (SARs) regime suffers similarly, with financial institutions providing mountains of intelligence to law enforcement agencies – intelligence that will inevitably fall through the cracks because of insufficient resourcing at the policing coal face.

Quantity v quality intelligence

This latest FCA set of priorities, if successful, will likely generate even more intelligence. There may be an argument that the quality of the intelligence may improve, but even if it does, it will still likely remain at the bottom of a hard-pressed, overworked investigator’s to-do-list.

New initiatives that effectively make the problem someone else’s issue are not the answer. To effectively tackle fraud as a national problem, the UK government needs to make it a policing priority. It is unacceptable for the government (and its agencies) to continue speaking in soundbites and deflecting from the clear shortcomings in its overall approach.

The primary issue at this time is not the dearth of information from the regulated sector – it is the fact that law enforcement and the regulators can’t cope with what they collect presently.

Tony McClements is head of Investigations at Martin Kenney & Co (MKS), an investigative litigation practice based in the British Virgin Islands.