If you have any remaining doubt about the significance of AI, consider The Gutenberg Principle. This has become the unit of measure for significance in communication, arguably significance in any number of fields.

It works like this. When anything is considered not just important but of world-changing significance, it is compared with the publication of The Gutenberg Bible in 1455, the first printed book to be produced using moveable type. The publication laid the basis for the mass production of books, and therefore the mass dissemination of information and knowledge. Power to the people, if you like.

Claiming something was the most important or significant development of all time invites counter-argument for its own sake. Suffice to say that the production of The Gutenberg Bible was pretty significant. Enough, in any case, to be used as a measure after the World Wide Web first appeared on Tim Berners-Lee’s computer at CERN in 1990 and observers needed to describe how significant this was.

It soon became common to see the web described as the most significant development since The Gutenberg Bible, and the penchant for parallels was boosted when a company called Moveable Type – named after Gutenberg’s printing technology – established itself as one of the early leaders in the field of blogging platforms.

“The development of AI … will change the way people work, learn, travel, get health care, and communicate with each other.”

Bill Gates

Given how fundamentally the web has transformed everything we do, and in such a comparatively short time, it could be argued Berners-Lee’s invention outstripped Gutenberg’s in the significance stakes. Information is now more widely distributed and easily accessible than ever, making the world a smaller place and, ironically, making it easier to find out that Gutenberg wasn’t the inventor of the printing process. The Chinese had been printing with wood blocks since about 800 AD, and a Chinese minister called Choe Yun-ui printed a lengthy Buddhist text called The Prescribed Ritual of the Past and Present using moveable blocks of metal in 1250.

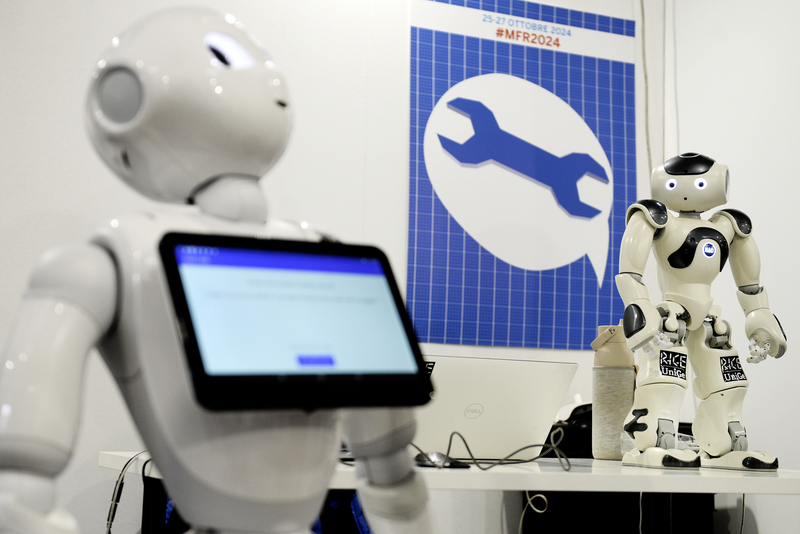

AI is the latest development in the field of information and communication to have The Gutenberg Principle applied to it. An example is robotics consultant Roger Smith’s 2017 article AI is the 21st Century Printing Press. Six years later the comparison has reached critical mass. And any lingering doubts about just how important the arrival of AI is were dispelled when Bill Gates pronounced The Age of AI has begun in an article on LinkedIn earlier this year. In it, he said: “The development of AI is as fundamental as the creation of the microprocessor, the personal computer, the Internet, and the mobile phone. It will change the way people work, learn, travel, get health care, and communicate with each other. Entire industries will reorient around it. Businesses will distinguish themselves by how well they use it.”

In short, everything is going to change. And when that prospect is on the horizon, people get nervous. The rise of AI has led to dystopian visions of a world in which the machines take over from the humans – the stuff of many a sci-fi horror yarn and perhaps now the existential fear of our age. Technological development has always led to worry about how it will be deployed, and discussion too often tends to settle into a knockabout between caricatures – one side depicted as dinosaurs, the other as eager fools embracing something the consequences of which they don’t understand.

Getting to grips with the change involves understanding the nature of the change, working out the opportunities it presents, and acting to mitigate any of its negative aspects. That’s the challenge for compliance and regulation professionals, and to meet that challenge it’s important to give some thought to the effect the increasing use of machine intelligence is likely to have on human beings and what we are able, and expected, to do.

Christian Hunt is a compliance professional who now specialises in applying behavioral science to compliance work. He has worked for a number of financial services organisations, and says in his LinkedIn profile that he came to realise that “we were in the business of influencing human decision-making. You can’t just tell an organisation to be compliant. It’s the employees you need to influence”.

Weighing up progress so far, Hunt says that “what we’ve been doing so far is replacing humans in predictable repetitive tasks. What that means for humans going forward is that we’re going to be using people for doing different things; things that involve skills like nuance, emotional intelligence, judgment. Things the machines are not capable of, and I stress this, yet.”

“What I find fascinating is that not only is there a risk with the technology, but there’s also a risk with the roles that humans are going to play.”

Christian Hunt

He goes on: “That’s when we are at our best as a species. We’re doing things that involve very human attributes. It also is when humans pose the greatest risk to organizations. If you look at when decision-making goes wrong, it’s often when we are emotional.

“What I find fascinating is that not only is there a risk with the technology, but there’s also a risk with the roles that humans are going to play, because we are putting people in positions where they can be amazing, but also where they can do appalling things.”

We discussed the fact that a good number of those involved in developing AI, including Geoffrey Hinton, who had been working for Google on machine learning and has been dubbed ‘the godfather of AI’ because of his leading edge work in the area, and OpenAI founder Sam Altman, have expressed fears about where the technology could be taking us.

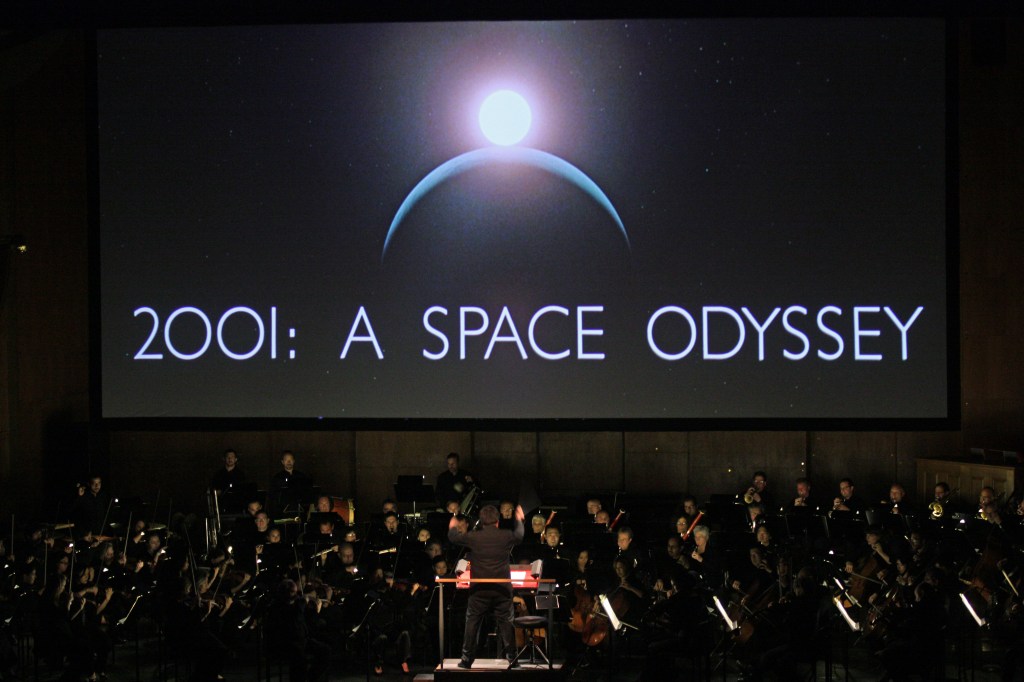

The letter issued by the Elon Musk-funded Future of Life Institute and signed by thousands of figures from the tech world earlier this year in which the view that “Powerful AI systems should be developed only once we are confident that their effects will be positive and their risks will be manageable,” was expressed represented a pivotal development. It prompted comparisons with the moment Robert Oppenheimer, who developed the atomic bomb, witnessed the first detonation of a nuclear weapon and recalled the words of the Bhagavad-Gita; “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds”.

Oppenheimer, of course, went on to devote most of his life to efforts to control nuclear power and limit weapons proliferation, and was perhaps in the thoughts of UN Secretary General António Guterres when he recently called for the establishment of something like the International Atomic Energy Authority to regulate AI. “The scientists and experts have called on the world to act, declaring AI an existential threat to humanity on a par with the risk of nuclear war,” he said. “We must take those warnings seriously.”

But, says Hunt: “What I think is interesting is if you’ve looked at previous technologies, and I’m talking about things like social media, generally speaking the narrative has always been incredibly positive. There was never this admission that there might be actually be a downside to it. So the one thing I think is refreshing at the moment is that at least we have an acknowledgement by the people that are putting this stuff out there that there is a potential risk.”

“We’re expanding the capabilities and the difference between a physical cognitive artificial intelligence and natural intelligence.”

Christian Hunt

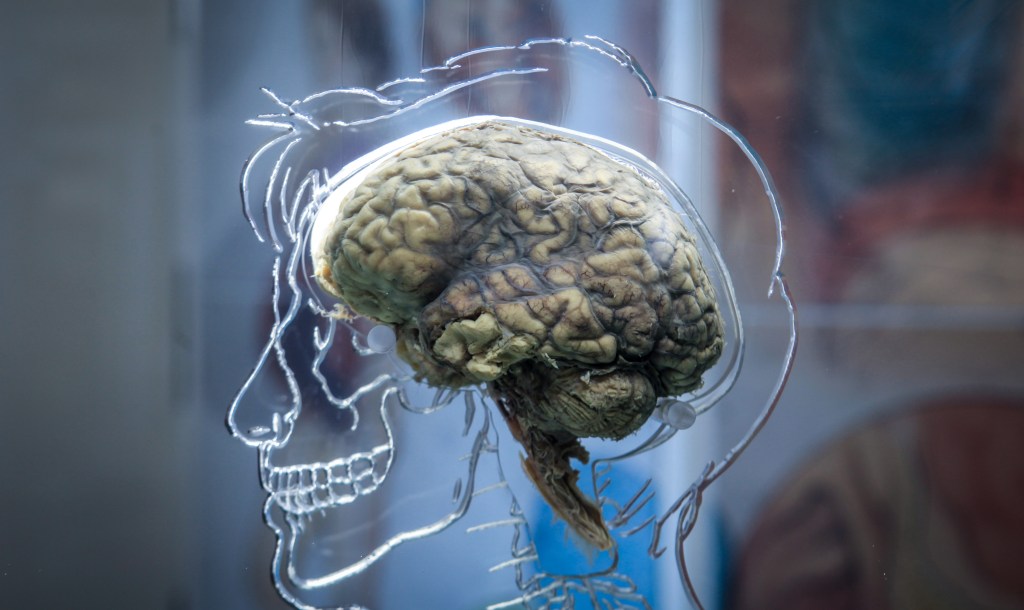

What we need to recognize, Hunt thinks, is that “we’re expanding the capabilities and the difference between a physical cognitive artificial intelligence and natural intelligence”. What this means is that our ability to imagine what a world in which AI plays a much greater part is compromised, “because we’re not able to think through all of the permutations … the things that we’re talking about will have capabilities and already have capabilities that extend beyond what we have in the human brain”.

Put simply, “we’re being asked to imagine the unimaginable” he says. “The advantages may well be well beyond what we are capable of thinking of. But the disadvantages may also be well beyond that. The truth, of course, will sit somewhere between those two things.”

That inability to imagine what we might have to deal with is something that regularly comes up. “What we’ve seen also is that governments and regulators have shown in many cases that they are not fully comprehending the scale of some of these issues,” says Hunt. “If you look at the scenes when Mark Zuckerberg sat in front of the Congress or Senate in the US, and they were asking questions about how Facebook made money…

“So one of the risks, and we see this a lot with technology, is that because of the scalability of it things can run well ahead of the regulatory position. We really do need regulators and risk managers and people within organizations to have a level of understanding of this that they’ve never had before. We’re going to need to upskill very, very quickly. There’s a requirement for regulators to step up to the plate. Rather than waiting for something to go wrong, we have to have regulation.

“From a regulatory perspective, what is this technology going to do? It is going to make the task that you have harder. Because at least when you are trying to police people, there are various bits of hold that we can put on them. When it comes to technology, that’s much harder for humans to do. So you’re going to need to have technology in place to be able to monitor the technology.

“That means you need to have people that are competent enough to create technology that can monitor and to keep an eye on it and to think not just literally about the problem, but to think laterally as well; to be thinking much more open-mindedly about the unintended second, third, fourth, fifth-order consequences of some of this stuff.

“Maybe regulation has to become more intrusive than ever before to manage some of these risks. Because we can’t let this just go on unchecked.”

Christian Hunt

“I’m not sure that we always have the right people in the regulator. I’m not saying we don’t have smart people there. I’m just saying we are treading in territory where knowledge and skills that were relevant in previous areas may no longer be as relevant. So we need to be adapting the people that we have, and that probably means putting more resources behind regulation. That means more money, and accepting the fact that regulation is going to be expensive.”

The most testing conundrum, says Hunt, is that “Maybe regulation has to become more intrusive than ever before to manage some of these risks. Because we can’t let this just go on unchecked”. Here, perhaps, we identify the true source of the fear underlying the debate, the growing realisation that it might not be the technology itself that poses a threat, but the way we have to adapt to it, the sacrifices we may have to make and the changes we have to embrace.

Certainly we are going to have to think much more rigorously about the information we receive and disseminate in the accelerated Information Century we now live in. Hunt expands. “Data comes from one place, which is the past. And the challenge with data coming from the past is that data is inherently biased. Even the best design systems will be relying to a certain extent on the data that’s put into them.

Photo: Matt Cardy/Getty Images

“So we need to start thinking about what it is that data telling us, what is that data missing. And one of the things that we know from the human brain is that we’re not very good at recognizing weaknesses in data sets. We are capable of making decisions based on the information that we have rather than the information that we should have.

“There’s much more male data than there is female data out there, for example. Men have held positions of responsibility because of the biases in our society. So when we feed information in, we’ve got to recognize the weaknesses in that and think about how we can compensate. Because otherwise what we’re going to be doing is scaling up based on data that’s inherently biased.”

Hunt firmly believes this means we need to know what to leave behind. “There are lots of skills and experience that we have picked up over time that are becoming less and less useful,” he says. “That’s not to say it’s useless, but it’s less and less useful. If you’ve been learning things in an analog world, they don’t necessarily apply in a digital world. Some of the things that we have been teaching children, and have been taught ourselves, that we think are potentially valuable might not be.

“We will need some people with specialist skills to retain some things, craftsmanship, for example, from the past, that we can make that we use to know what the machine should or shouldn’t be doing. So we can’t forget everything. But for the average person, I think there are going to be skills that are no longer going to be incredibly useful.

“We ought to be looking at very human skills like creativity and being able to recognize, you know, what things that we have that make us more human. And so as the machines are taking over more of our tasks, we’re going to be doubling down on being more human.

“We’ve got to avoid assuming that what got senior people to the positions that they are in now is necessarily going to be the useful skill set for the next generation.”

Christian Hunt

Critical thinking becomes absolutely essential as we start to look at what is truth.

“One of the things I thought was really interesting about things like ChatGPT is what a core skill to get the most out of ChatGPT and not to be misled by it is. To know how to ask smart questions and to understand the answers that you’re given. The ability to ask a good question is not a skill that we necessarily pick it up. Being able to ask better questions, understand answers – that stuff becomes really important in the world that we’re moving into. Or probably the world that we’re already in, actually.”

So how does this apply to financial services? Hunt says: “We are not spending time training people on things that are not deep technical skills. So you’ll learn what derivatives are and how they work. And if you’re a regulator, you’ll learn about liquidity in capital and those technical subjects.

“What we’re not doing is equipping people with the skills that allow them to navigate this particular landscape, things like social trends and digital literacy, for example. Forward thinking companies are providing training in subjects that five, 10 years ago, you probably wouldn’t have thought had anything to do with work.

“Everybody is going to have super smart brains within their organization, because this tech is freely available. So the question then comes to what’s your strategic advantage? And the answer is you need people to be thinking differently. Hiring smart people is going to become a baseline. So we’ve got to avoid assuming that what got senior people to the positions that they are in now is necessarily going to be the useful skill set for the next generation.”

If the debate over what AI means for us is to move on usefully, we are going to have to be a part of the change in order to be able to understand it. The focus so far has been on how the technology will operate, but it is becoming increasingly clear that the crux of the debate – certainly if we are to fully embrace opportunity as well as fully understand threat – is going to be about how the presence of that technology changes our experience as human beings.