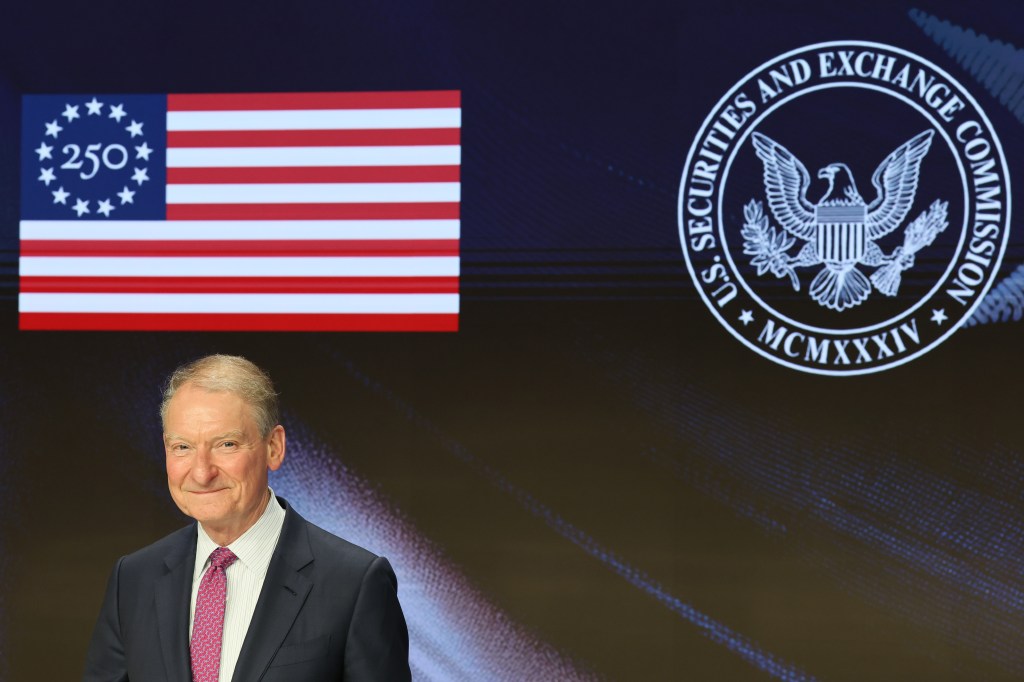

Paring back certain disclosure requirements that are contained in Regulation S-K, all of them rooted in the concept that businesses must disclose what is financially material to investors, was the subject of a recent speech by SEC Chair Paul Atkins.

At a Texas A&M University School of Law Corporate Law Symposium event, Atkins spoke about a possible “safe harbor” for publicly traded companies looking to avoid shareholder lawsuits for failing to report the impact of highly publicized events on their businesses, and providing detailed compensation information for the business’s top executives each year. He also touched on the need to modernize the treatment of executive security as a perk.

Let’s take a deeper dive.

Reg S-K

Regulation S-K outlines the required non-financial, narrative disclosures for public company filings (for example, 10-K, 8-K, IPO registration statements) that govern the standardized reporting on the business and its legal proceedings, risk factors, executive compensation, and related-party transactions. The disclosures are meant to focus specifically on information material to investor decisions.

Atkins focused on materiality in his remarks, noting that businesses must also scale their material disclosures to their “size and maturity.”

The SEC took its first step in reforming Reg S-K last May by soliciting public comments and hosting a roundtable on its executive compensation disclosure requirements. This set the stage for his remarks in Texas.

Executive comp

Atkins mentioned the executive compensation information businesses must supply for up to seven executives in a given year. He wondered about the scope being justified, and he quotes a comment on the SEC’s proposed rule change in this arena: “With the exception of the [CEO], the volume of detailed information … about the remaining [executives] is often immaterial to investors and, if anything, tends to obscure the information that they generally seek.”

Atkins said his agency should “reconsider the number of executives for whom compensation information is provided to appropriately calibrate the level of disclosure with cost.”

He also said he has asked staff to explore possible reductions to the pay-versus-performance rule that requires public companies to justify executive pay to shareholders by comparing it with the company’s financial performance. “Unfortunately, all of the time and money spent on PvP disclosure has scarcely resulted in clear information to investors,” Atkins said.

Executive security as a perk

Atkins said that he thinks an area that absolutely must be revisited is “the treatment of executive security as a perk.” When the SEC first created the rule around it (SEC Release No. 34-54302) in 2006, he said, the agency reasoned that “personal security services were not ‘integrally and directly related’ to job performance.”

But (without referring to the CEO of UnitedHealthcare who was gunned down in front of a hotel in Manhattan) Atkins said “the world has changed.” He said a commenter was correct in noting that “executive security is critical to the ability of many executives to perform their duties.”

Risk factors

He lamented that “risk factor disclosure,” which moved from just being in prospectuses to being in annual and quarterly reports, has become (in the typical Form 10-K) “one of the longest sections of the annual report.” He said it was originally intended to be a description for companies to list in a concise way “what keeps management up at night.” Although Item 105 in Reg S-K requires a summary if the risk factor section exceeds 15 pages, many companies have chosen “to keep their lengthy disclosures and add a summary on top of it,” he said.

Atkins said one solution for deciding what goes in this section is for the company or even the SEC to “maintain a set of risks, which could be published separately outside of the annual report, that broadly apply to most companies across most industries.” He said these “could include impacts from US legislative and regulatory developments, geopolitical issues, and natural disasters” and “serve as a form of ‘general terms and conditions’ associated with any investment in securities.”

And if the fear of being too concise is the threat of litigation, the SEC could “potentially [offer] a safe harbor from liability” if those risk factors are pretty generic and “are reasonably likely to affect most companies.” Therefore, not including them “will not constitute material omissions for purposes of some or all of the federal securities laws’ anti-fraud rules.”

Changes to N-PORT

A day after Atkins spoke in Texas, the SEC proposed amendments to N-PORT, the form used by most registered investment companies to report portfolio-related information. The SEC said its “changes are designed to reduce reporting burdens without significantly affecting the SEC’s use of the data or the public’s ability to assess relevant information about a fund.”

Form N-PORT is the reporting form required by SEC Rule 30b1-9 for monthly reports of most funds. Funds must report information quarterly about their portfolios and each of their portfolio holdings as of the last business day, or last calendar day, of each month, with some exceptions. Reports on Form N-PORT must disclose portfolio information calculated by the fund for the reporting period’s ending net asset value.

The proposed amendments to Form N-PORT are:

- Provide reporting funds with an additional 15 days to file monthly reports of portfolio-related information on Form N-PORT, which is designed to reduce the potential for errors and resubmissions.

- Reduce the publication of reports from monthly to quarterly, a change designed to protect a fund’s shareholders by reducing the risks of more frequent public disclosure, such as external parties using information about a fund’s portfolio holdings in ways that increase costs for the fund and its shareholders.

- Modify Form N-PORT reports to streamline or remove certain reported information, including removing “Names Rule” reporting, and add information about funds with share classes that operate as exchange-traded funds.

Author’s note

In September 2023, the SEC adopted amendments to the Investment Company Act “Names Rule,” which addresses fund names that are likely to mislead investors about a fund’s investments and risks. At the time, SEC Commissioner Mark Uyeda dissented from the decision to adopt the rule, saying the release provided little guidance and practically any term could be subject to the Names Rule.