In a landmark decision on October 14, 2025, the Swiss federal administrative court ruled that the March 2023 decree by the Swiss regulator, the Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA), was unlawful. The FINMA decree had wiped out CHF 16.5 billion (approximately $20.5 billion) of Additional Tier 1 (AT1) bonds issued by Credit Suisse in connection with its rescue and takeover by UBS Group AG.

The Swiss court ruling found that the FINMA action lacked the clear legal basis required under Swiss law. At the same time, in the United States, a separate legal action in New York saw international bondholders’ claims dismissed on the basis of sovereign immunity. These decisions raise international considerations for investor protection, regulatory power in bank rescues, cross-border jurisdiction, and the hierarchy of claims in bank resolution cases.

Legal framework and key findings

In the Swiss case, the Federal Administrative Court held that FINMA’s decree interfering with bondholders’ property rights lacked a clear legal basis. Neither the Swiss Banking Act nor the Financial Market Supervision Act was found to provide an adequate legal foundation for the action. In addition, a portion of the ordinance issued by the Swiss government authorizing the write-off was found to be unconstitutional, as it violated the property rights of the bondholders and exceeded limits on emergency powers.

The court found that the write-off of the AT1 bonds constituted serious interference with property rights, which under Swiss constitutional and administrative law requires legislation or a formal regulation, not merely a regulatory decision.

Moreover, the court questioned whether the prerequisites for triggering AT1-bond loss absorption were met, concluding that at the time of the write-off, Credit Suisse was still meeting capital requirements and had not triggered full resolution as envisaged under the resolution regime.

In practical terms, the ruling leaves some key questions unanswered. While the ruling revoked the prior FINMA decree, it did not result in a full reversal of that decree. The ruling also did not yet mandate that the bondholders be repaid or reinstated. Further proceedings will determine whether restitution or compensation is due to bondholders, and the decision is subject to appeal.

Cross-border implications

The Swiss ruling underscores that the Swiss government and regulatory bodies cannot assume they have the power to extinguish investor rights without a solid legal basis for doing so. This principle applies even in the context of “emergency” situations, including in the context of a bank resolution involving a systemically important bank with respect to domestic, regional and global financial stability.

The ruling also sends a signal that sophisticated debtholders such as AT1 investors, while they certainly assume significant investment risk inherent in making such investments, still benefit from constitutional protection of basic property rights. This is a key distinction between risk of performance of an investment and risk of state (or state-sanctioned) expropriation. In this context, even “exceptional” rescue measures approved at the highest levels of government must provide a clear legal justification that is well founded upon the existing legal framework.

For future bank resolutions, the case sets a precedent that resolution tools (especially loss absorption instruments) may be vulnerable to legal challenge if the statutory framework is not clear or is not strictly followed. It has become clearer that bank resolution tools will increasingly emphasize robust loss-absorption instruments as regulators push for stronger resilience and faster interventions. However, the Credit Suisse case shows the need for greater standardization, clearer creditor hierarchies, and improved cross-border coordination in implementing such instruments. As financial products evolve, bank resolution regimes must be adapted to maintain credibility, market discipline, and systemic stability within a predictable legal framework.

While the Swiss ruling stops short of identifying who must pay (the Swiss government, FINMA, or UBS), and the extent of such exposure remains to be determined, it places the liability question squarely on the table. In the AT1 bondholder case this liability could mean major compensation obligations for stakeholders and there may be difficult issues in assigning responsibility amongst private and public actors. Assuming full compensation is to be made as required under domestic Swiss law, regulators and courts will be faced with the thorny issues of determining who must compensate the AT1 bondholders and to what extent, particularly given the condition of Credit Suisse on the eve of the takeover.

US litigation and jurisdictional dynamics

The US legal front took a different turn in the AT1 drama. A group of AT1 bondholders filed suit in the US District Court for the Southern District of New York seeking approximately $370m in damages from the Swiss Confederation, arguing that Switzerland had unlawfully wiped out the bonds. The court dismissed the claim on September 30, 2025, holding that Switzerland enjoyed sovereign immunity under the US Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA).

The outcome of the US case has several important legal implications for international investors:

- First, sovereign immunity is likely to be a hurdle to such actions globally. Even where investors believe they have strong claims, sovereign nations may be shielded from suit in US and other courts unless a specific exception to sovereign immunity applies. However, suits against private actors with a sufficient jurisdictional nexus could be different.

- Second, the US case shows the limits on choice of forum to seek a more favorable outcome. As the United States is perhaps the most likely venue for success in extraterritorial claims of many types, if claimants do not succeed there, this serves as an indication that any relief may be confined to domestic actions.

- Finally, the US decision underscores strategic investor considerations in bringing such cases. The costs to litigate such matters can be significant, particularly in jurisdictions where success was thought to be more likely, such as the United States. Investors holding foreign-issued instruments will need to assess all of the risks and potential costs of litigation in another forum.

Swiss and US decisions

These dual developments – a favorable Swiss ruling and an unfavorable US dismissal of their action – have added further complexity to what was already a complex cross-border legal landscape for AT1 bondholders and for the future of other creditors and investors in cases of potential expropriation involving government intervention and large financial institutions.

From the Swiss perspective, bondholders now have renewed hope. The ruling that FINMA’s action was unlawful provides a basis for damages or reversal of the write-off. While the largest financial institution workouts have been outside of Switzerland (many in the United States), perhaps these cases will provide, if not a blueprint, at least insight into issues that must be addressed in working out a solution for bondholder claims that is legally sound and accepted by the markets.

On the US side and internationally, however, the dismissal of the case in New York means that investors cannot rely on US courts to pursue the Swiss government, and this is likely an indicator that extra-jurisdictional action is unlikely to succeed, at least against the government. Absent another forum, enforcement and compensation will now hinge on Swiss law.

The combination could ultimately create a jurisdictional patchwork and make bondholder claims more difficult to sustain across borders. A party could have a successful substantive claim under Swiss law, but practical obstacles in enforcement and recovery if the counterparty is a sovereign or if the liability falls outside normal avenues for litigation.

Finally, the conflicting rulings may have a signalling effect. The Swiss ruling may shift the bargaining position of bondholders significantly. Even though the US litigation route failed, the domestic Swiss case may become the primary pathway to a remedy, and the value of claims may indeed increase accordingly. However, the limitations based on the state of Credit Suisse prior to the takeover will need to be considered and could serve as an ultimate limitation on the value of any claims.

Broader implications

Beyond the Credit Suisse case, the rulings carry broader significance. While the Swiss ruling heralds a material change, much about the ultimate outcome remains uncertain and the ruling is subject to appeal to the Swiss Federal Supreme Court. FINMA has already launched an appeal, and UBS has indicated that it will also appeal the ruling.

Even if the FINMA decree is revoked, the court has not yet decided whether the bonds must be reinstated or whether damages will be awarded, and if so, by whom. The cost could be borne by state and non-state actors, including the Swiss government or UBS.

AT1 bonds and similar instruments used by regulators to absorb losses in stressed banks may come under increased scrutiny, both by investors and at a policy level. Even such “designed to fail” instruments require clear legal triggers and regulatory transparency if they are to serve their intended function as both an investment opportunity and a fail-safe mechanism. If the rules are ambiguous, bondholders may assert their rights under other legal avenues, resulting in instability and uncertainty.

Regulators may face correspondingly greater scrutiny when acting rapidly in crisis modes, limiting their effectiveness. The idea that acting in a systemic “emergency” should allow broad curtailment of investor rights is under pressure. Authorities will need to ensure they are on a robust legal footing to sell future actions, both to the courts and to the markets.

International financial institutions with cross-border capital raising implicate multi-jurisdictional challenges. What appears to be lawful action in one jurisdiction may be challenged in another. Sovereign immunity, choice of forum issues, and differences in investor protection regulations remain key considerations.

Investors in bank capital instruments may increasingly price not just traditional credit risk but also consider structural and regulatory risk. The prospect of regulatory cancellation may now be seen as more than a mere technicality in market pricing of these instruments. In Switzerland and elsewhere, the case may ultimately prompt legislative and regulatory reform to clarify how write-offs are triggered, the scope of bondholder rights, and more specifics about regulatory obligations in bank rescue schemes.

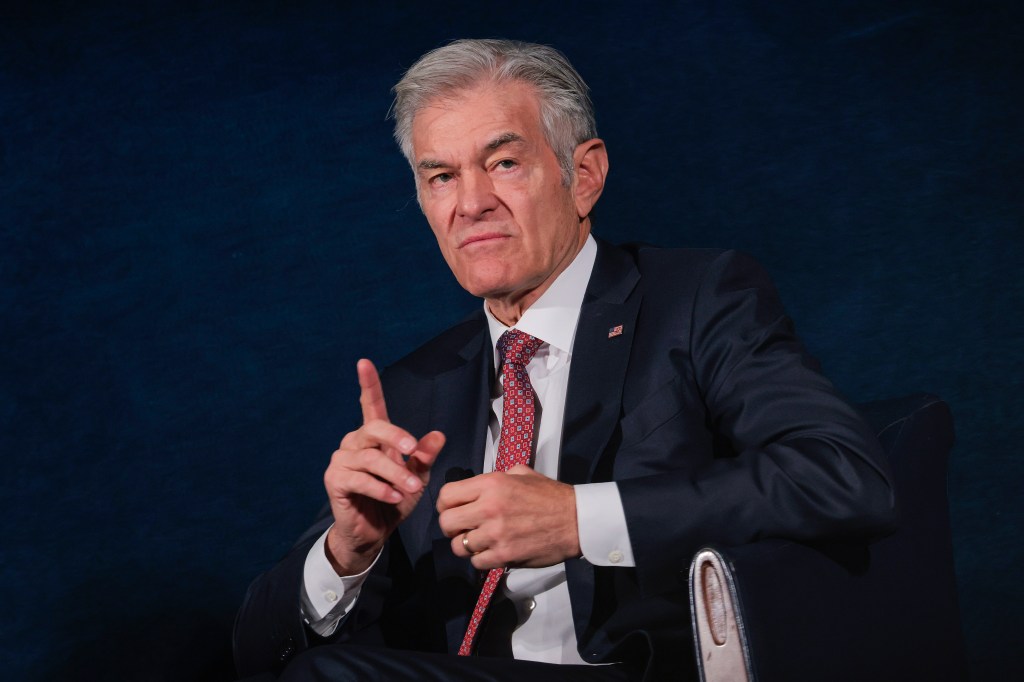

Gregory Walsh, International Tax & Wealth Management partner at Spencer West Switzerland.