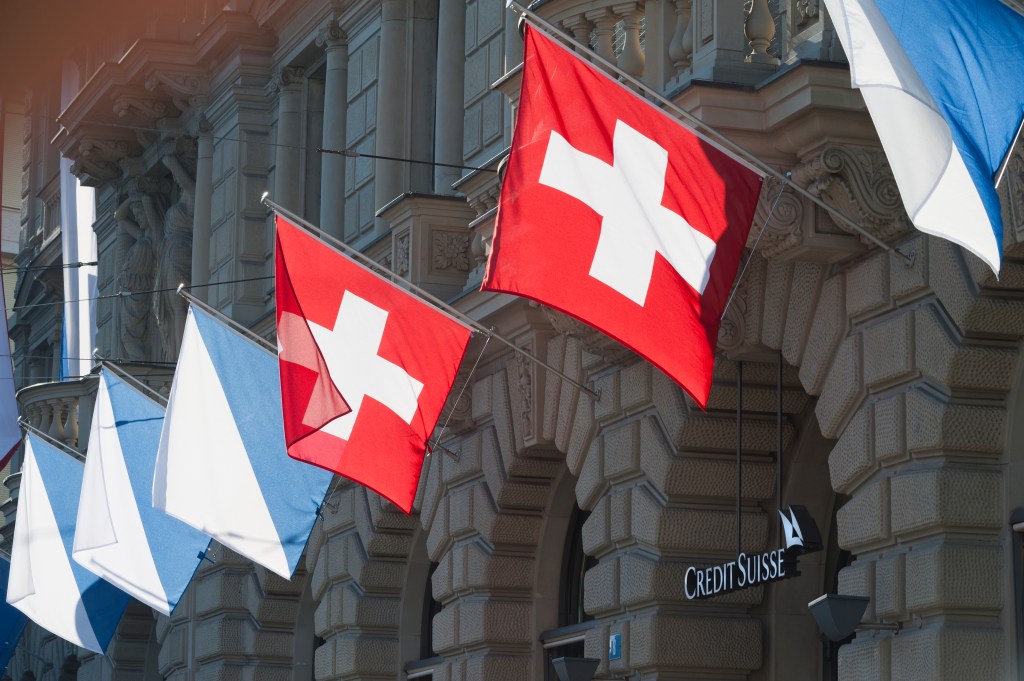

UBS has now taken over its previously formidable competitor, Credit Suisse (CS), after a sequence of events which led the CS share and bond prices to come under such intense pressure that global regulators felt obliged to mandate a takeover to ensure financial stability.

CS was renowned for its strong capital foundation as an emblematic, 166-year-old bastion of Switzerland, projecting stability, neutrality and consistency. It was also renowned for managing some of the world’s wealthiest private individuals, and regarded as the prime example of reliable and safe Swiss banking.

Back in 2008, the credit crisis gripping the banking sector had made UBS particularly fragile – along with LIBOR, FX and rogue trader scandals. CS had not been so affected by the crisis and these other issues. At that time, there was considerable speculation that Credit Suisse might bail out or take over UBS.

Because Credit Suisse was less damaged than its peers, it felt less incentive to change and take the same remedial medicine that its competitors were obliged to take.

The crisis resulted in an intense period of remediation for many institutions that had faced negative regulatory as well as macroeconomic outcomes; this resulted in a review of strategy and a wholesale refocus on the supervision of their activities, with particular emphasis on risk and compliance controls.

Because CS was less damaged than its peers, it felt less incentive to change and take the same remedial medicine that its competitors were obliged to take.

Over the next decade, a regular stream of headline-grabbing scandals emerged. These included:

- a spying scandal and personal vendettas at Board level in Zurich leading to the ousting of the CEO;

- Greensill allegations of fraud resulting in $10bn of investor funds being put at risk, a fraction of which was recoverable;

- Archegos (the high-risk hedge fund that masqueraded as a family office) leveraged trades which resulted in CS as the most damaged prime broker, suffering an alleged $5bn trading loss, the largest ever suffered by CS;

- the new CEO’s cultural and conduct issue which revolved around breaching Covid restrictions and seemingly excessive use of the corporate jet for personal travel;

- client bribery and embezzlement issues related to Mozambique and other financing activities linked with a Bulgarian cocaine smuggling ring;

- and a regular flow of exposure for some other clients proving less than desirable from a reputational perspective.

At the time and at the most senior levels, a message of remorse and reform was consistently espoused, but the long list of misdemeanors suggested that despite these sentiments, tangible action and investment in strengthening controls and driving any real cultural change was limited.

Good oversight of risk

Doing monitoring and supervision well requires appropriate levels of resourcing to have meaningful reports and the right talent and technology to review data, identify and escalate issues. A vital piece of this is effective governance that is supported by senior management to then take appropriate action. The compliance team was making every effort to maintain effective oversight during these difficult times.

The key question is whether any issues they might have uncovered as part of their BAU were suppressed or overlooked as part of ‘a profit at any cost’ culture that seemingly prevailed during this time.

It is also worth mentioning that the unique rules around Swiss secrecy were diluted though not entirely removed at this time, making the country less attractive to some investors. The invasion of Ukraine compounded the pressure on CS.

The very fact that culture at that level was not setting the right example sent the message to those lower down that their conduct could be similar.

“The Board of Directors is responsible for the overall direction, supervision and control of the Credit Suisse Group” according to the bank’s website. Some of the issues mentioned above stemmed directly from the behavior of the most senior leaders in the bank. The very fact that culture at that level was not setting the right example sent the message to those lower down that their conduct could be similar.

Pursuing positive financial results at any price appears to be the logical explanation for some of the higher risks that backfired – risky investments others had elected to avoid.

Despite the problems, the lack of fundamental change in risk oversight by significantly raising budgets to resource the controls teams with enhanced data, improved technology and bigger teams would also explain the lack of desire to uproot these cultural problems.

Big scandals don’t just happen. There are always some clues. Compliance and risk monitoring exist to identify and escalate suspicions, some of which must have related to these very issues. Effective communications surveillance should obviously identify regulatory breaches but it is also a key way of flagging conduct and behavioral concerns. The nature and variety of the offences, the extended period of time over which they were happening, and their pervasive nature, must have been evident in communications that should have been identified with efficient monitoring.

What happens next?

The critical change to improve culture and invest in well-resourced teams, effective controls, smart technology solutions, and some added ‘insurance policies’ undoubtedly moved the needle and led to positive outcomes in managing prevailing risks in other institutions. Many have been close to the point of no return but managed to turn around; Deutsche Bank, and UBS ironically, may be the best examples of this.

Regulators are now also implicitly looking at ‘minimum control standards’ and questioning why some firms deem it reasonable to identify and prioritise their risk, but only then deploy the minimum controls to manage it.

Strong compliance and risk oversight should be seen by the Board as an investment in the future and security, rather than a cost or loss that results in competitive risk to the business.

There will always be firms who cut corners but the risk run can, in extreme cases, prove fatal.